Patriarch Dositheus II of Jerusalem and Saint Peter Mogila are of importance on the question of baptism, because the former’s confession and the latter’s catechism have attained to Pan-Orthodox reception, which makes them dogmatic authorities of a sort.

Saint Justin Popovic, in Volume 2 (1), Chapters 6-7 of his Dogmatics discusses the nature of such authorities:

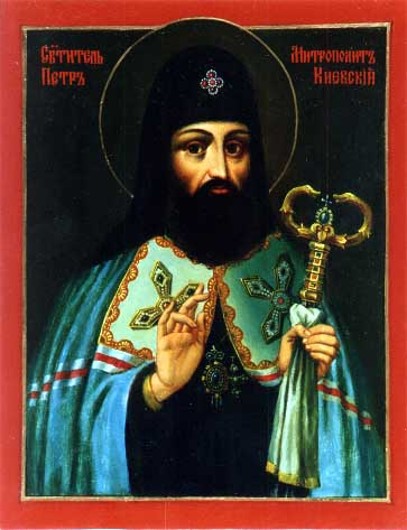

Dogmas in the Church have always been dogmas, both before and during and after Councils…Of the statements of faith of a later period, which are not approved and approved by the Ecumenical Councils, and therefore are significant only insofar as they are consistent with the one, holy, catholic and apostolic teaching of the Ecumenical Church of Christ, expressed in the symbols and creeds of the ancient Church…[are the] “Confession” of the Jerusalem Patriarch Dositheus, approved in 1672 by the Jerusalem Council and in 1723 sent to the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church on behalf of all Orthodox patriarchs as an example of an accurate statement of faith. Accepted by the Russian Holy Synod…[and the] “Orthodox Confession” by Peter Mogila, Metropolitan of Kiev, examined and corrected at the Councils in Kiev in 1640 and in Iasi in 1643, and then approved by all Orthodox Patriarchs and published under the title “Orthodox Confession of the Eastern Catholic and Apostolic Church”.

One may interpret the preceding to mean that these councils are secondary to the Ecumenical Councils. However, being that one always works with the presumption of consistency between the fathers, canons, and councils, the difference appears to be that of emphasis. We do not harmonize the earlier conciliar teaching in light of these later councils. Rather, the opposite is the case.

Being authoritative in this qualified sense, the question is whether the Councils of Jerusalem (1672) and Iasi (1643) taught consistently with the earlier tradition on the question of baptism. It suffices to say that both presume upon baptism having proper form and their teachings taken in the proper context do not appear to violate earlier canonical tradition.

Dositheus (Jerusalem 1672). Dositheus requires that baptisms have correct form. Decree 15 of the Council of Jerusalem, in a recent translation, is rendered thusly:

We also reject, as something unclean and polluted, the teaching that some imperfection of faith prevents the celebration of the sacrament. For heretics – whom the Church accepts after they renounce heresy and join the [Orthodox] Catholic Church – despite their imperfect faith, they receive perfect baptism, and therefore, when they further acquire perfect faith, they are not rebaptized. (Quoted in “On the Reception of the Heterodox into the Orthodox Church,” p. 285)

There is some debate concerning how to interpret this passage. Some favor the idea that heretics have perfect [i.e. valid] baptisms by default and so they are not rebaptized. Others, namely Father Theodore Zisis and Monk Seraphim Zisis who made the above translation from the Greek, argue that “Dositheos [sic] is not addressing the topic of ‘validity’ of the baptism of those outside of the Orthodox Church but is addressing the question of whether the operation of the Holy Spirit in the Mystery relies on the degree of faith of the person baptized” (Ibid.), something that appears to be a direct response to Cyril Lukaris’ Decree 15:

But that the Sacrament be entire and whole, it is requisite that an earthly substance and an external action concur with the use of that element ordained by Christ our Lord and joined with a true faith, because the defect of faith prejudices the integrity of the Sacrament.

In other words, the Decree is not even about baptism outside the Church, but how baptism is efficacious within the Church. Saint Philaret of Moscow’s gloss of the Greek appears similar, presuming that “when they renounce their heresy and join the universal Church, received perfect baptism, although they had imperfect faith.” (Source)

Not presuming upon the Zisis reading, one may speculate the presumption is that the passage pertains to heretics with baptisms that strictly have perfect form. With such a reading, there is a parallelism between perfect baptism and perfect faith, the one being perfect beforehand and the other only occurring upon entering Orthodoxy. Additionally, the idea that heretical baptisms are valid no matter what, though a possible reading, seems to import a lot of meaning that is not there.

However, even if the parallelism falls apart in light of the Zisis reading, Decree 16 ironically makes the same point anyway. The Decree contains sundry details on the subject. It details the proper “matter” of baptism (“pure water, and no other liquid”) and “words.” It likewise makes the dry observation that:

Baptism imparts an indelible character, as does also the Priesthood. For as it is impossible for any one to receive twice the same order of the Priesthood, so it is impossible for any once rightly baptized, to be again baptized, although he should fall even into myriads of sins.

Clearly, Dositheus’ logic which may potentially be inferred from Decree 15 is explicitly found here. One is not “again baptized” if “once rightly baptized” just like a priest’s ordination is never repeated. Improper matter, at minimal, would require another baptism. This appears to be a slap against Cyril Lukaris’ Decree 16, which disallows all rebaptism:

But concerning the repetition of it [baptism], we have no command to be rebaptized, therefore we must abstain from this indecent thing.

Obviously, Dositheus (contra Lukaris) is saying one only abstains from rebaptizing provided it was initially done “rightly.” As a subsequent section will cover, Dositheus not only implies the necessity of correct form, he most certainly adhered to the idea–making it the only inference one can draw from his own Decree 16. Therefore, while Dositheus does adopt the economic approach to baptisms outside the Church, he is explicitly endorsing correct matter and form as per the canons.

Mogila (Iasi 1643). The version of Peter Mogila’s catechism received by Iasi 1643 explicitly requires that baptism have correct form. Baptism, according to Mogila, requires “proper Matter” and “[t]he invocation of the Holy Ghost, and a solemn form, words.” (p. 75) While one may be tempted to interpret the “solemn form” as simply pronouncing the correct words “[b]y which the Priest celebrates the Mystery,” (Ibid.) Mogila shortly afterwards plainly states:

Baptism is a washing away and rooting out of original Sin, by being thrice immersed in Water; the Priest pronouncing these [w]ords: In The Name Of The Father, Amen; And Of The Son, Amen ; And Of The Holt Ghost, Amen. After which[,] regeneration by Water and the Spirit a Man is restored to the Grace of God, and the Way opened him into the Kingdom of Heaven…this Mystery being once received, is not to be again repeated ; provided the Person who administered the Baptism believed orthodoxly in Three Persons IN One God, and accurately, and without any Alteration, pronounced the afore-mentioned Words. (p. 75-76)

Shortly later, the same idea is repeated:

[L]awful Baptism must necessarily be administered by a minister of the Word only, unless in Case of urgent Necessity, when any other Person, whether Man or Woman, may administer this Sacrament; being observant to use the proper Requisite, namely, unmixed and natural and pure Water, and dipping the Person to be baptized thrice therein, repeating the solemn Form of In The Name Of The Father, And Of The Son, And Of The Holy Ghost, Amen. And this Baptism, which is not to be again repeated… (p. 76-77)

In the preceding, the solemn form is coupled by specific wording. And so, one is compelled to understand the catechism approved by Iasi demands traditional Orthodox matter and form “without alteration” as normatively necessary for baptismal regeneration.

Potential Inconsistencies with Earlier Tradition. Dositheus and Mogila speak of baptism’s “indelibility” and invoke proper “intention.” Both of these categories of thought appear to lack explicit emphasis in earlier tradition.

Considering “intent,” at first glance, it appears to contradict Sacred Tradition. In fact, certain hagiographic details such as Saint Genesius of Rome’s mock baptism and Saint Athanasius’ childhood baptismal gameplaying were events where baptisms lacking literal intent had real salvific grace. However, “intent” according to Dositheus and Mogila probably (though not explicitly) carries a specific Thomistic meaning which applies much differently. In short, Aquinas’ doctrine of “intent” effectually makes baptisms with wrong form passable as they allegedly have the same intent as those with correct form (Summa, Third Part, Question 66, Article 8, Reply to Objection 3).

Thomas Aquinas (simply identified as “Thomas”) was cited by Cyril Lukaris in a section quoted favorably by Dositheus’ Jerusalem Council. (Source, p. 31) While this is too tangential to infer an outright blanket acceptance of every idea Aquinas ever had, it does make it reasonable to infer that “intent,” not being a category of thought from the Orthodox tradition, is presumed to have its Thomistic meaning as this is where Dositheus and Mogila would have found the idea. Aquinas, like Tertullian, was treated with some authority.

Aquinas and Dositheus were against baptisms with defective form. Aquinas asserted that “trine immersion is universally observed in Baptism: and consequently anyone baptizing otherwise would sin gravely.” (Summa, Third Part, Question 66, Article 8, Answer) Dositheus taught that:

For they who (without necessary cause) are not baptized with three emersions and immersions are in danger of being unbaptized. Wherefore the Latins, who perform baptism by aspersion, commit mortal sin. (Quoted in “On the Reception of the Heterodox into the Orthodox Church,” p. 288)

From the preceding, one now has the necessary context to correctly interpret what Dositheus decrees on baptism. Specifically, baptism must have correct form (as we already established). Incorrect form is a mortal sin (i.e. unrepented of, damnation is the result—a stark warning) for the one performing it and the one receiving the baptism is potentially unbaptized. Clearly, one cannot interpret Dositheus to be acting outside the obvious canonical understanding of earlier authorities that required correct form when employing economia in the reception of the heterodox.

In Mogila’s and Dositheus’ documents, the Thomistic doctrine of “intent” appears to be appropriated in order to explain how proper economically-received baptisms were acceptable (i.e. emergency baptisms which cannot be done by full immersion, baptisms done by pouring due to lack of water, baptisms performed in baptisteries as opposed to in rivers due to logistical constraints bearing upon good church order, etcetera). Hence, “intent” does not like a wand make all baptisms with incorrect form suddenly equivalent to those with correct form (which appears to be how Roman Catholics have wrongly appropriated Aquinas’ idea, as clearly he would have not wanted Roman Catholic ministers to “sin gravely” on this question). Rather, it explains how economic considerations (in the Didache, for example) work.

In fact, if one were authentically following Jerusalem 1672, one could not possibly allow for almost any Western baptism in the modern day (Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Presbyterian, etcetera) because of their lack of necessary cause for incorrect form (i.e. their lack of proper “intent”). Therefore, Dositheus’ specific Thomistic gloss actually allows for a harmonization with hagiographic tradition which permits for baptisms with proper form completely lacking intent to be efficacious, because “intent” for all practical purposes only applies to baptisms with improper form.

To make it simple, a baptism with correct intent is one where the correct form would have been used if it was possible. One cannot infer a permissiveness for the violation of form on purpose.

Now let’s discuss how “indelibility” squares with Sacred Tradition. If baptism with proper form can exist outside the Church, what does one make of Apostolic Canon 46, which deposes bishops who allow for the “baptism or sacrifice of heretics.” This appears to contradict the indelibility of baptisms of those outside the Church with proper form. However, it does not have to, as the correctness or incorrectness of form is not explicit in the canon. Rather, Apostolic Canon 50 requires a baptism by “three immersions” deposing those doing only one immersion—so clearly the presumption is form must be correct in the Church and there would be no basis that improper form is somehow acceptable outside the Church. A legalist may recognize that the question of form, unsaid by Apostolic Canon 46, means the canon only applies to said baptisms with improper form.

I prefer the tact that Saints Basil the Great and Nicodemus the Hagiorite take. One can reconcile the Apostolic Canon with Mogila and Dositheus by presuming that the Apostolic Canon expresses the ideal is to disallow for all heretical baptisms, but economia permits those with proper form to be accepted and not in violation of the canon. One would deal with “Cyprian’s Canon,” which limits baptism to “being existent only in the catholic Church,” similarly. Ultimately, this is precisely what Saint Dionysius of Alexandria, who gave a favorable estimation of Cyprian’s conciliar work on the question, (Eusebius, Church History, Chapter 7, Par 5) effectually did during the time the canon was even issued. While accepting Cyprian and Firmilian’s hardline stance, his own stance was economic and deliberately contrasted with Saint Stephen of Rome. Therefore, such a reconciliation categorized by Basil or Nicodemus is hardly an interpretative stretch, but literally fits the historical context of the time Cyprian’s Canon was issued.

Granted, especially in Saint Cyprian’s case, there can be no doubt that his purpose was to exclude Novatian schismatics despite their proper form (whose baptisms are accepted by the canons, such as Canon 95 of Trullo). The Apostolic Canons likely shared this purpose. This is a literal contradiction of the economic allowance that Dionysius of Alexandria championed. But the tension created by this contradiction, preserved by Trullo itself which endorses Cyprian’s canon as well as the Apostolic Canons, creates the effect that the canons exhibit both the ideal and what is permissible (i.e. akrevia versus economia). So, neither are incorrect, ideal, or exclusively the teaching of the Church. They are both correct, which is why the canons preserve both. In light of the preceding, indelibility can be easily harmonized into Sacred Tradition provided it is not the exclusive approach to the question of baptism.

Potential Conflict with Saint Peter Mogila’s Trebnik (Service Book). So far, it has been established that the explicit teachings of Mogila and Dositheus within documents of theirs received by a Pan-Orthodox consensus harmonize with the canons and Sacred Tradition. However, do they jive with Mogila’s own teachings elsewhere? In a word, no.

In the Trebnik, Mogila equates full immersion with “the infusion of water on the top of the head through the whole body” calling them “the first or second form of baptism” respectively. (Trebnik, p. 215—translated from the French in Antoine Wenger’s “La réconciliation des hérétiques dans l’Église russe. Le Trebnik de Pierre Moghila“) Elsewhere he states plainly, “Holy baptism is perfectly accomplished both by the immersion of everything (the subject) in water and by the infusion of water on the top of the head through the whole body.” Ibid., p. 8) He also explicitly accepts the baptism of “the Anglicans and the Calvinists, and other similar sects.” (Ibid., p. 154)

Would this require one reading Mogila’s catechism contextually to conclude it contradicts the intent behind Jerusalem 1672? Also in a word, no. Iasi 1643 boasted of “purging it from all foreign defilements and novelties” from Mogila’s catechism and only afterwards:

confirmed it with their approbation, as containing the true and genuine doctrines, and in nothing departing from the sincere and catholic faith of the Greeks; and declared it to be pure and uncorrupt, by the universal judgement, determination, and consent of all. (Source, p. 8)

Hence, due to the council only explicitly prescribing full immersion and Jerusalem 1672 (a Greek council received by the Slavs instead of the other way around) expressing the view of Dositheus, it is most plausible that the conciliar mind of Iasi did not endorse the thought expressed in the Trebnik. They would have adhered to the Greek view, as they literally said above. Being that Mogila himself delivered Iasi’s edited document back to Kiev, this implies tacit consent from Mogila of any modifications performed to his work.

Conclusion. The conciliar documents attached to Dositheus and Mogila surely cannot be appropriated as justification for the more liberal applications of economia in the modern day, as the conciliar views of baptismal form of Iasi 1643 and Jerusalem 1672 were much more strict and traditional. The preceding indicates that Constantinople 1755 was not as drastic revision of earlier precedent as it is usually believed (though the council made no specific allowance for proper form, it implies it). Hence, the majority (not universal) Russian practice of permitting two forms, like the Trebnik specifies, proves to be a regional custom that defies consensus as delineated in Iasi and Jerusalem. It also lacks antiquity on the question of form. By the “Vincentian Canon,” one would be forced to see the custom as a regional and a historical aberration.

As for Iasi and Jerusalem, by my estimation there are no contradictions with their Latin theological terminologies and Orthodox application as expressed in the canons and Sacred Tradition. Following Saint Justin Popovic, as long as we don’t put the cart (Mogila and Doistheus) in front of the horse (Sacred Tradition preceding their day), we find the teachings of all to be quite complementary and hardly creating any sort of irreconcilable difficulties. Further strengthening this view is that the harmonization I expound here is from the third century and it was precisely that harmonization which ended the baptism spat between Saints Stephen of Rome and Cyprian of Carthage.

For those who express concern about what is one to do about the world’s largest Orthodox jurisdiction for centuries following an aberrant practice (or seemingly most the Orthodox world doing the same today), first I would remind such people to remember the Vincentian Canon. Even if a near-consensus adopts such a practice, without being from antiquity, it cannot be correct. Second, I will quote Saint Cyprian:

The Lord is able by His mercy to give indulgence, and not to separate from the gifts of His Church those who by simplicity were admitted into the Church, and in the Church have fallen asleep. Nevertheless it does not follow that, because there was error at one time, there must always be error. (Epistle 72, Par 23)

Cyprian’s response to whether such correct reception is necessary for salvation is not necessarily, because we always presume upon God’s mercy. In other words, it is not the end of the world that some people have begun adhering to Mogila’s view that pouring is a secondarily acceptable form. All those received by the Russian custom are indeed full Orthodox Christians, as any other conclusion would be incomprehensible. However, just because something is not absolutely necessary, as God is merciful, it does not mean we should act lawlessly. Perhaps, instead of agonizing over there being an existential crisis of some sort (as proper form is a necessity), we should affirm all is well, but that we can do better. If it were not for the authority of Sacred Tradition, which includes Iasi and Jerusalem, I would not be able to confidently express this view.

Postscript: Some Additional Thoughts on Emergency Baptism. Saint Basil’s first canon states the following:

…after breaking away they became laymen, and had no authority either to baptize or to ordain anyone, nor could they impart the grace of the Spirit to others, after they themselves had forfeited it. Wherefore they bade that those baptized by them should be regarded as baptized by laymen, and that when they came to join the Church they should have to be repurified by the true baptism as prescribed by the Church. (Source)

From what I can glean, many Orthodox tradition’s Book of Needs allows for “emergency baptisms” by laymen, but if the recipient pulls through the baptism is to be repeated by a priest. (Greek source; Macedonian source) So much for an unyielding application of the logic of indelibility. Yet, Saint Rafael of Brooklyn (then under Russian jurisdiction) calls such emergency baptisms “valid” (i.e. efficacious) and only prescribes chrismation if a child pulls through. (Source) Similarly, New Martyr Daniel Sysoev calls the sacrament “valid” and instructs someone in Sri Lanka that at some later time they can get a child chrismated by a priest and then he can commune. (Letters, p. 163)

Nevertheless, emergency baptism appears to be a widely received pastoral basis for the repetition of a sacrament (“conditional baptism“). Due to the potential for disorder in the Church, a layman’s baptism is to be rejected—even with proper form—unless absolute necessity requires it (now “intent” kicks in). It would seem that one cannot reduce to a binary whatever is valid is always not repeated, despite indelibility.

Wow. Great work. The ending just closed a small historical chapter for me in my own life and that of my children. Much appreciated.

Wow. I’d like to know how!

Thank you, this post was helpful. However, a somewhat minor issue: Unless I’m missing something, the linked source about St. Raphael of Brooklyn says that if the emergency lay-baptized person pulls through they should then be chrismated by a priest. It doesn’t say anything about repeating baptism.

TY, I made a correction and added another citation from Fr Daniel Sysoev where he takes the same view.

Much ado has been made in some circles on the “indelible” remark in Decree 16. Would it be fair to say that while this terminology may have been borrowed from the Latins, EO doctrine does not endorse the Latin “indelible mark” of the priesthood?

I have not reflected on this carefully, so take the following comment with a grain of salt. Indelibility does not always apply with conditional baptisms. Furthermore, the canons specify for the rechrismation of apostates. So, if a priest apostatizes (or is a novatianist) he is rechrismated. It would seem that orders are not again conferred if he is turned into a Orthodox priest as a former Novatian. This seems to follow the logic of baptism (the form of ordination was followed and Chrismation completes everything, I suppose there’s nothing the Holy Spirit cannot do).

However, I don’t think priests lacking the Holy Spirit can do a “valid” liturgy in private, as the RC view of indelibility speculates about their priesthood.

Also, to be totally transparent, I am not very concerned with the correct answer to this question. What is the practical import? If the priest is not in the Church, he is irrelevant to us. If he is reincorporated into the Church, then it should be done in good order.

I would be seriously interested in a strong, dogmatic defense of the Russian practice which integrated so many Uniates without *allegedly* even Chrismation (I prefer someone actually cite something specific on this question because people disagreeing on these matters are so divisive its hard to trust anything). Father Daniel Sysoev gives a consistent, but troubling answer: the RCs are still in the Church! The Pope was never deposed! They go to Hell for being heretics, but not schismatics. Of course this can work, but it seems to me to ignore way too much history on the question of schism. It to me exposes the unworkability of the Russian program the last few centuries. But what is impossible with man is made possible with God. Perhaps that’s the chief lesson we should be drawing from all of this.

A quote from St Macarius of Jerusalem: “However, should there be a sick person where there is neither church nor regular font, it is not right to prevent the person willing to baptize, the baptism may be administered without a regular font, *because* the circumstances compel, lest he be found a debtor for salvation by obstructing baptism.” (Letter to the Armenians; Terian, p. 81)

As for the expected form for baptism in all other cases:

“And by triple immersion being buried by waters of the holy font, we signify in the persons of those who are being baptized the three-day burial of the Lord.” (Ibid., p. 85)

The preceding shows that Dositheus is consistent with the Didache, Macarius, and the Thomistic doctrine of intent that economic allowances are valid based upon *necessity*, something I don’t here people making clear enough.