Nothing makes Protestants balk more at Orthodoxy than the practice of praying to the saints, particularly to Christ’s mother. This is not without reason. In short, the objections to the practice may be summed up as both practical and theological.

Practical Objections. The practical objection can be summed up as, “Why waste my time praying to Mary when I can just pray to God.” In short, it is an efficiency-based argument which presumes we should be maximizing our prayer utility.

There are several obvious errors with this way of thinking–namely the presupposition that God desires our prayer life to be very efficient. If we should not be asking the saints for their prayers because it “wastes time,” then why ask anyone to pray for us? Or better yet, why even bother praying? God already knows what we need before we ask.

So, let’s dismiss the efficiency-based objections to prayers-to-the-saints because they are not serious objections. Let’s focus on the theological objections.

Theological Objections. The first objection Protestants usually put forward is that asking the saints for prayers is necromancy. As we have discussed previously, this is not a strong objection because 1. necromancy has a specific meaning which is obviously ignored by people who raise such an objection and 2. prayer and veneration do not meet the Biblical standard of worship.

The second objection is much more compelling and it can be summed up as follows: prayers to the saints are not in the Scriptures nor are they prominent in early Church history.

The preceding is a serious objection which cannot be hand-waved away with an unthinking “sola scriptura is false” sort of counter-argument. Think about it for a moment–if the practice is not in the Scriptures, then we lack a first century attestation. If it is not in the writings of the church fathers, then we lack historical evidence of the practice. This being the case, what historical basis would we have to reject the assertion that the practice is a later innovation? We would be forced to appeal to the infallibility of the Church, but this appeal is only convincing to those who have already drank the Koolaid. It does not appeal to those who are making an honest inquiry into the truth.

To answer the previous objection, I will make three points:

First, we will show that it is reasonable to trust the Church.

Second, we will briefly review the earliest historical evidence we have for prayers to the saints.

Lastly, we will offer our most compelling evidence of all–that we do not have evidence of early Christians rejecting the practice (with the exception of an outlier named Vigilantius.)

Trusting the Church. Fathers, with a high view of the Scriptures, saw no contradiction between believing that the Scriptures were materially sufficient (i.e. they contain all necessary Christian doctrine) and petitioning the saints for prayers.

Let’s take Saint Athanasius for example. After all, he wrote that “divine Scripture is sufficient above all things” and discounted novel Arian doctrines because “in the divine Scripture nothing is written about them.”

Yet, Saint Athanasius has a Marian prayer ascribed to himself and almost certainly was petitioning Mary in the anapohras of the Egyptian liturgy and praying the sub tuum praesidium. Obviously, he believed there to be no contradiction between such prayers and the Scriptures (which states all generations will bless Mary in Luke 1:48 and exalts the prayers of the righteous in James 5:16).

Why cannot Protestants simply write off Saint Athanasius (and Ambrose, Jerome, and pretty much every single saint that we have writings from after the fourth century) as being misguided in this one respect?

The reason Protestants cannot is because it creates epistemological mega-problems for Christianity. The modern doctrine of the Trinity, Christology, soteriology, and the Biblical Canon itself were all formulated in the fourth century. Why would we depend upon Saint Athanasius, Jerome, Ambrose, or whomever to understand what books are actually in the Bible if they were glorified polytheists, praying to Mary as if she were a demigod?

It would seem that if these men were outright heretics in their prayer life, then they would not be trustworthy authorities for anything. It would be like trusting the Mormons to tell us which books are in the Bible.

In reflecting upon this issue, I cannot help but think of Saint Augustine’s way of grappling with the question of the Bible’s trustworthiness. He wrote:

I felt that it was with more moderation and honesty that it commanded things to be believed that were not demonstrated (whether it was that they could be demonstrated, but not to any one, or could not be demonstrated at all)…After that, O Lord, You, little by little, with most gentle and most merciful hand, drawing and calming my heart, persuaded taking into consideration what a multiplicity of things which I had never seen…I believed of what parents I was born, which it would have been impossible for me to know otherwise than by hearsay — taking into consideration all this, You persuade me that not they who believed Your books (which, with so great authority, You have established among nearly all nations), but those who believed them not were to be blamed…For now those things which heretofore appeared incongruous to me in the Scripture, and used to offend me, having heard various of them expounded reasonably, I referred to the depth of the mysteries, and its authority seemed to me all the more venerable and worthy of religious belief, in that, while it was visible for all to read it, it reserved the majesty of its secret within its profound significance (Confessions, Book VI, Paragraphs 7 and 8).

The preceding is a mouthful, but it is important. Let me sum up Augustine’s argument as follows:

- The Scriptures require us to believe things that must be accepted by faith and lack demonstration.

- God gave him the conviction that we accept things all the time on good authority without demonstration, such as who our parents are.

- Hence, on good faith, Augustine accepted the Scriptures because when he heard them “expounded reasonably” he saw that they made sense.

- This gave him confidence that whenever he personally could not understand a certain Scripture in a reasonable way, he withheld judgement against the Scriptures because they were overall trustworthy.

- In such situations he would embrace the mystery of what he did not understand on the authority that whenever he had tested the Scriptures they were found trustworthy.

The preceding is an extremely compelling argument for the Scriptures–we accept them to be true, even when they may seem confusing, because whenever they are put to the test they have always proven themselves to us. If we can apply this epistemological argument to the Scriptures, then surely we would trust the authority of the Church, who has proven Herself correct with the Canon of the Scriptures, the preservation of their manuscripts, the defense of Christological doctrines from them, and all other things.

It would seem that the Church has earned the benefit of the doubt. So, if she preserved the practice of petitioning the saints, it is eminently reasonable that even if we do not fully understand their Scriptural basis, we would take it on good authority that it is there and embrace the mystery.

Early Historical Evidence of Petitions to the Saints. Many assert that prayers to the saints are a very late innovation. After all, the fourth century is 300 years after the time of Christ. A lot can change. For example, the USA was a collection of British colonies and Indian tribes three centuries ago!

That being said, it would be untrue to say that the earliest we see Marian veneration is in the fourth century. We have compelling historical evidence, accepted also by Protestant scholars, that we have third century Marian prayers (the above referred anaphoras and the sub tuum praesidium.)

These were preserved in Egypt. This was probably due to the climate which helps preserve very old manuscripts, the wealth of the Church of Alexandria which helped the proliferation of written documents (which increases the chance of their preservation for posterity), and the relative hands-off policy Rome treated their wealthy Egyptian province.

How do we know that Marian veneration was not some sort of Egyptian practice that later spread like a cancer? First, the sub tuum praesidium exists in slightly altered forms in all parts of the eastern and western church. This makes it less likely that it spread from Egypt itself. Rather, the document we have in Egypt was merely a prayer written down that was already widely disseminated.

Second, the contemporary liturgies copied in the fourth and fifth centuries (Liturgy of Saint James, Saint Basil, Saint Chyrsostom, etcetera) have invocations of the saints and requests for petitions. This is extremely unlikely without the practice being widespread, being that the creedal statements and sections of these liturgies have corroboration in second century (Saint Ignatius’ and Saint Irenaeus’ quoting of creeds) and third century (Saint Hippolytus’ Apostolic Constitutions) documents. We have are good grounds for believing, being that the fourth and fifth century liturgies agree ad verbatim with second century documents, that the later liturgies are simply the earlier liturgies in full written form.

Third, we potentially have second century evidence of Jewish prayers to the saints. One passage of the Talmud, dated between the second and third centuries, serves as an example:

Caleb held aloof from the plan of the spies and went and prostrated himself upon the graves of the patriarchs, saying to them, ‘My fathers, pray on my behalf that I may be delivered from the plan of the spies’ (Sotah 34b).

In light of the preceding, we must ask ourselves: what is the chance that both the second and third century Christians and Jews prayed to saints, over a large geographic spread, and that this does not represent a pre-Christian practice that was continued during the Apostolic age?

Early Christianity’s Allergic Reactions Against Innovations. In light of all of the preceding evidence, someone who rejects petitions to the saints may argue that the practice might have been a Jewish syncretistic holdover that latched somewhere onto the first or second century Church . Thereafter, it spread like cancer to the point it was common everywhere in the third and fourth centuries.

Yes, this is an argument from silence and obviously a conspiracy theory, but is it at least a sensible one? I think anyone who has studied early Church history and understands the culture of early Christianity and its successor, the Orthodox Church, would realize such a conspiracy theory is not workable.

Being that none of us can time-travel into the past, one way a modern Protestant can understand ancient Christian culture is by simply stepping foot into a modern Orthodox Church. Here, one would find when speaking to many Orthodox, particularly clergymen, an obvious stubbornness to compromise over matters that appear disputable (i.e. terminology, worship practices that are not doctrinal, etcetera). It seems to many that Orthodox are curmudgeons unwilling to level with us and just have a normal conversation.

Here is an example: I once asked the Deacon in my church why they watered down the blessed wine (what people drink after communion) with water instead of grape juice. He gave me a stare, thinking I was talking about the Eucharist, and then said coldly, “Because we only use water, and that’s all we have ever done.” Pertaining to the Eucharist, he is correct, as even in the third century Christians were already strict about mixing only water with wine (Cyprian, Letter 62, Par. 9). In fact, not mixing water with the wine was a major no-no (an interesting fact in that the Scriptures do not explicitly mention this practice).

To non-Orthodox this seems to be overly-scrupulous. Over-scrupulous or not, this sort of mentality prevents people from getting rid of things easily. It may be difficult to understand the preceding without firsthand knowledge of Orthodox worship and regular interaction with Orthodox. Nonetheless, I think the concept is helpful to have some familiarity with when discussing the conspiracy theory that prayers to saints were an innovation that somehow “snuck” into the Church somewhere and then spread like wildfire.

Why? Because we have examples of regional practices and innovations in the early Church. Likewise, we have examples of how Christians responded to them. The following early Church disputes have been recorded for us, showing that even small and seemingly trivial things did not go unnoticed without extensive debate:

- The date of the Easter celebration in Ephesus differed with the whole Christian world, resulting in councils and even an excommunication (mid to late second century)

- The Roman Church’s custom of accepting the baptisms of Christological heretics likewise resulted in councils and an excommunication as well (mid third century)

- Paul of Samosata, the Bishop of Antioch, taught that Jesus Christ was not the Word made flesh–resulting in his universal condemnation (mid third century)

- Saint Dionysus of Alexandria, in response to Paul of Samosata, used theologically imprecise language and as a result described Jesus Christ as a created being. The Egyptian and Roman Church rejected this teaching, and Dionysus recanted (mid third century)

- As part of the preceding debate, the term “of the same substance” was rejected due to Paul of Samosata’s usage of the term in denying the Trinity.

- The Council of Nicea described Jesus Christ as “the same substance as the Father.” This language was used previously by Paul of Samosata and so its connotations were disagreeable to many. Almost the whole Church later rejected the Council of Nicea over the meaning of this word and only four decades later did the doctrine of Christ’s same substance and essence gain wide acceptance. The reason for the debate ultimately was not because Bishops disagreed with Nicene doctrine but that they were distrustful of Nicea’s terminology. Only when the world’s Bishops were convinced that the terminology more accurately presented Trinitarian doctrine than any other options did the Arian controversy end. (early to late fourth century)

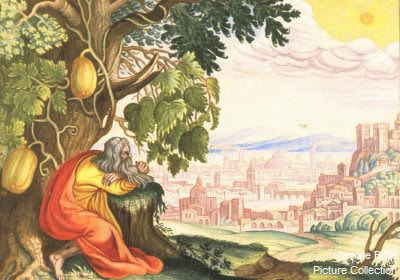

- Saint Jerome translated the Book of Jonah from the Hebrew and riots (Augustine, Letter 75, Par 22) broke out because he replaced the word “gourd” with “ivy” (late fourth century)

The preceding is not an exhaustive list, but this much is clear–if the Church experienced tumult over the day of Easter, the usage of an extra-biblical Greek term to describe Christ’s divinity, and even the inclusion of the word “gourd” into the Book of Jonah, it seems unthinkable that Marian prayers would start somewhere and then spread without notice. The intellectual atmosphere in early Christianity would have not permitted it. Yes, this is an argument from silence, but as they say, “the silence is deafening.”

Conclusion. In short, we may conclude the Orthodox pray to the saints on good authority in that:

- It being “a waste of time” is a baseless argument.

- Prayers to the saints is not “necromancy,” because necromancy has nothing to do with prayer.

- It’s widespread acceptance and huge importance in historic Christianity for 1500 years, the same Church that bequeathed us the Scriptures and all things Christian, cannot be ignored.

- Solid historical evidence exists that the practice existed during the centuries of Christian persecution by the Roman Empire and that it likely began as a pre-second century Jewish practice.

- If praying to the saints was antithetical to Christianity, it is almost unthinkable that it would have passed by without debate–when Christians even found the time to riot over the removal of the word “gourd” from the Book of Jonah.

In light of the preceding any reasonable person would conclude that without definitive grounds to object to the practice of praying to the saints, that they must be accepted. To not do so ultimately belies an unreasonable approach to Christianity itself.

Peter–

Yeah, your position seems closer to that of the very early church, who honored their saints but did not pray to them. Instead, they thanked God that (presumably) the departed faithful prayed for them.

Craig likes continuity but cannot show that EO distinctives go all the way back. It’s an Achilles’ heel.

Christ is the is the source of all this, but the Christians (on earth or heaven) are called to share in these roles as an instrument of God. As subordinates to Him. We are supposed to be doing these things for one another as members of the Body of Christ (communion of saints). The ultimate glory goes to Him.

Peter, btw, if you ask for someone to pray for you or they just do it on their own that is called interceding on your behalf. Full stop.

Grace my mind. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Teach me to step aright. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God? Strengthen me to keep awake in song. – only God can do this. No subordinates?

Drive away the sleep of despondency– only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Release me from my bonds of sin. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Guard me by night and by day. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Deliver me from foes that defeat me. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Enliven me who am deadened by passions. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Enlighten my blinded soul. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Make me to be a house of the Divine Spirit. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Heal the perennial passions of my soul. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Guide me to the path of repentance. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Deliver me from eternal fire. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Let me not be exposed to the rejoicing of demons. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Renew me, grown old from senseless sins. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Present me untouched by all torments. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Vouchsafe me to find the joys of heaven. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Hearken unto the voice of thy servant. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Grant me torrents of tears. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Raise me above this world’s confusion. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Direct the grace of the Spirit in me. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

Deliver me from soul corrupting evils. – only God can do this. No subordinates to God?

1. I think that a lot of people forget what “pray” even means–even in English. It just means “petition” or “ask.”

2. I think some of the prayers literally refute their view that the prayers are henotheistic. FOr example, “Guide me to the path of repentance.” If we ask the Theotokos for this petition, don’t we wonder why? Repentance does not set us right with the Theotokos. We are asking for her help in our worship of God–not of her.

Exactly! THEY remove Jesus as the source and then become scandalized.

God wants us participate with Him, but as subordinates of Jesus not as equals.

Plenty of people thank Billy Graham for bringing them to Jesus and I would venture many people sought him out to find answers and come to believe because of him . There is nothing wrong with saying this as long as one understands it was the work of the Holy Spirit and Gods grace and BG was merely Gods instrument, unless of course, you insist as Hans does, that unless you specifically say it was the work of the HS and Gods grace you must be worshiping Billy.

It’s silly.

CK

I don’t deny that saints are to be honored. We are to affirm that they worship and pray with us. They also pray for us. We can ask god to hear their prayers and ours . I am not taking the

typical Protestant line of

complete disconnect with the

church above.

You missed the point that I was conveying by the distinction I made between someone already praying for you and asking that someone to pray for you. I was rejecting the claim of Craig that if one affirms the former than one must as a logical consequence accept the latter. That simply is not correct. Brother smith can intercede for brother jones with out necessarily brother jones making any request to brother smith for such intercession.

The litany of questions you ask only reinforces the blurring of distinction that I mentioned in my previous post.

Craig-

I would ask you go back to my original post. What I say there is hardly the a typical Protestant lament which condemns all IOS. The beef I have is the type of IOS that you defend. In all due respect, I am fully aware of EO apologetics’s on “Mary save us” prayer. It is an example of the “giving with the right hand but taking away with the left hand” argument. You convey a meaning but than undermine the meaning by the language used. You ask me “do you really think that we believe that she atones for our sins?” No Craig, I don’t. Neither do I think that you believe Mary is your savior, or that you believe she saves you by her own power. But that is exactly why then it wrong to pray that. All of your qualifying does not justify language that belongs to the lord. Only he is to be called upon to save. Rc/eo apologists are emphatic that prayer to saints is analogous to us simply asking our brothers/sisters to pray for us. But “Mary save us” is beyond that, it is similar how we would and ought to pray to god.

“Only he is to be called upon to save. ”

Seriously? First give me a list of individual words I can only use when speaking to God and can’t be used when speaking to a human being.

I’ll start it for you:

1. save

You sound like those evangelicals that insists you should call no man “father”.

So if I fall of a boat and ask Joe Six Pack to “save me” instead of “rescue me” (oops only God can rescue me from death, so can’t use that) so I guess I have to be very specific. Joe throw me a line! If I do make it out alive I need to make sure I don’t say “Joe thanks for saving me” because God will get mad at me.

By the way, not all prayers is worship. Prayers to God always is worship.

You all get caught up with words and completely ignore the heart. It’s very protestant.

CK–

I don’t at all maintain that the boundaries are clear between worship and veneration. I’m looking mostly for the attitude of the heart, but in prayer that will necessarily involve words. You act as if your words don’t matter as long as you can vaguely categorize them as “not intentionally worshipful.” To my mind, that lacks any sort of humility, any desire on your part to be utterly SURE that you’re not crossing the line. If someone accused ME of idolatry, I would do an intense inventory of the interplay between my heart and my practice in prayer.

Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart is famous for attempting to delineate indistinct borders:

“I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description [“hard-core pornography”], and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it, and the motion picture involved in this case is not that.”

Personally, I don’t see how the prayers in question could be seen as anything other than idolatry (regardless of the stated intention). There are simple fixes available which you could use but refuse to entertain. If nothing else, you are likely causing others to stumble (and you don’t appear to care).

Ck,

Not only am serious, but what is sad is that you know full well what I meant by he alone is called upon to save. Not from drowning, from failing a math test, etc… But saving ones soul from damnation. Your illustration fails. Yes, only the Lord should be called call upon to save ones soul. That’s why the scripture says call upon the name of the lord to be saved. Not Mary, not St. Peter, not st, Teresa, but the Lord. Please, don’t waste ink with passages that speak of humans saving in a subordinate sense. None of those passages actually teach to invoke (call upon) human persons to save our souls. That is a key distinction. I find it mind boggling that you guys will go to such lengths to make a clear distinction between invoking saints and prayer to God, but then completely utilize and defend certain Marian prayers that completely obliterate the distinction. When your called out for it, you respond with ad hominem attack on Protestants caught up with words instead of the heart. (Note: actually modern day Protestants have rejected liturgy for emotionally based worship. )

H-But saving ones soul from damnation. Your illustration fails. Yes, only the Lord should be called call upon to save ones soul. That’s why the scripture says call upon the name of the lord to be saved. Not Mary, not St. Peter, not st, Teresa, but the Lord. Please, don’t waste ink with passages that speak of humans saving in a subordinate sense.

Me- ok I’m back to thinking you don’t understand the communion of saints. The communion of saints is a tool given to us to use by God. You can choose to tell Him you don’t need it, I do.

You say saints pray for us. What could they be possibly be praying for? What is their ultimate goal when they pray for us? In Hebrews we are told we are surrounded by witnesses. They are encouraging us on in this race. They are are playing their part in saving our souls.

What is your goal by getting me stop praying to the saints? What are you trying to do for me? You are playing what you believe is your part in saving my soul.

All this grace comes from God and he will be the ultimate judge. But we are called to help one another. God doesn’t care how I come to Him in the end because it’s through His Grace working through you or Mary etc…. All the glory belongs to Him and all grace flows from Him.

Those in heaven will be playing a role in our judgment. Of course the King will have the final say.

Do you not know that the saints will judge the world? And if the world will be judged by you, are you unworthy to judge the smallest matters? Do you not know that we shall judge angels? How much more, things that pertain to this life? (1Cor. 1Cor. 6:2-3).

4 I saw thrones on which were seated those who had been given authority to judge. And I saw the souls of those who had been beheaded because of their testimony about Jesus and because of the word of God. They had not worshiped the beast or its image and had not received its mark on their foreheads or their hands. They came to life and reigned with Christ a thousand years. Rev 20-4

So with this understanding I can say you can save me as can Mary as instruments of God. This is the communion of saints.

So let’s keep this simple. Do agree with anything I just wrote?

CK–

There’s a grain of truth to what you say.

That’s the problem!!!

We are made in the spirit and image of God. So, in every good and decent thing we do, we emulate him.

But there is also a creator-creature divide (even in Catholic theology). In this sense, he is inimitable. We cannot perfectly recreate his actions. Not now, and not in the world to come!

He has graciously given us great gifts. We can paint beautiful canvases using every shade of indigo and orange and green and violet. What we cannot do–and never will be able to do–is to create a fourth primary color. Red and blue and yellow are all that we will ever have.

So yes, ordinary people can guide us, strengthen us, and enliven us. But we basically NEVER ask them to. They may also comfort us or enlighten us. But who ever instructs a friend to “comfort me in my sorrow”? Don’t we rather tell them, “I miss him (or her) so much!!” while weeping on their shoulder?

We only say the words “enlighten me” in a sarcastic manner to those whose thinking we do not respect. To our actual mentors, we only exclaim, “I can’t figure a way out of this mess I’m in!!”

Certain ways of speaking are appropriate for family members which are not appropriate for friends which, in turn, are not appropriate for romantic interests…which are not appropriate for God.

I may care for and even, in some sense, love a woman who is not my wife. But I better not use the same “love words” on her unless I want to see a frying pan hurled across the room aimed at my head!

***********

“Spanish is a loving tongue,

Soft as music, light as spray.

Was a girl he learned it from,

Living down Sonora way.

He don’t look much like a lover,

But he says her love words over.

Mostly when he’s all alone:

“Mi amor, mi corazon.”

************

What bothers me about your stance, CK, is that you don’t even WANT to hold back on the “love words” you use with those who are NOT your Lord! It’s fine with you if they cannot rightly be differentiated. Christ will understand!

*************

Recognize this?

“Mary, lover of my soul,

Let me to thy bosom fly,

While the nearer waters roll,

While the tempest still is high.

Hide me, O my Lady, hide,

Till the storm of life is past;

Safe into the haven guide;

Oh, receive my soul at last.

“Other refuge have I none,

Hangs my helpless soul on thee;

Leave, ah! leave me not alone,

Still support and comfort me.

All my trust on thee is stayed,

All my help from thee I bring;

Cover my defenseless head

With the shadow of thy wing.”

**************

Some Evangelical “Contemporary Christian” songwriters are criticized for not differentiating enough between love of Christ and earthly romantic interests. In this way, the passion we have for our Lord can be trivialized. These are jokingly called “Jesus is my boyfriend” songs.

I think you’re doing something similar.

Hans

You are hitting it on the nail! ! Very good. It is the language that is incredibly troublesome. For those who pray that and not as theologically astute as Craig and ck it is even more problematic. Add to that our idolatrous tendencies that plaque us, even more troublesome.

H-We are made in the spirit and image of God. So, in every good and decent thing we do, we emulate him.

CK- agree

H-But there is also a creator-creature divide (even in Catholic theology). In this sense, he is inimitable. We cannot perfectly recreate his actions. Not now, and not in the world to come!

CK-Never said we could but because we can’t it doesn’t mean we hold back. We are to emulate Him as you said above.

H-He has graciously given us great gifts. We can paint beautiful canvases using every shade of indigo and orange and green and violet. What we cannot do–and never will be able to do–is to create a fourth primary color. Red and blue and yellow are all that we will ever have.

CK-You insist that’s what we are trying to do. We tell you no but it doesn’t matter. For you (and God apparently) cares more about words than the heart.

H-So yes, ordinary people can guide us, strengthen us, and enliven us. But we basically NEVER ask them to. They may also comfort us or enlighten us. But who ever instructs a friend to “comfort me in my sorrow”? Don’t we rather tell them, “I miss him (or her) so much!!” while weeping on their shoulder?

CK-What? In your world, if I turn to someone to comfort me in my sorrow and use those words I’m offending God. If I use different words God is not mad. Again, in your world, what’s in one’s heart doesn’t matter to God but rather the words used do! This is so legalistic!

Catholics believe what’s in your heart is really what matters in the end.

Your view implies that if I repent with words but not heart I’m forgiven but if I use the wrong words but repent in my heart I’m not forgiven.

H-We only say the words “enlighten me” in a sarcastic manner to those whose thinking we do not respect. To our actual mentors, we only exclaim, “I can’t figure a way out of this mess I’m in!!”

CK-You does not make a “we”.

H-Certain ways of speaking are appropriate for family members which are not appropriate for friends which, in turn, are not appropriate for romantic interests…which are not appropriate for God.

CK-I guess those in a court of law in England are all going to hell. They refer to the judge as your “worship”. Surely that’s only appropriate for God.

H-I may care for and even, in some sense, love a woman who is not my wife. But I better not use the same “love words” on her unless I want to see a frying pan hurled across the room aimed at my head!

CK-Your wife is not God.

H-What bothers me about your stance, CK, is that you don’t even WANT to hold back on the “love words” you use with those who are NOT your Lord! It’s fine with you if they cannot rightly be differentiated. Christ will understand!

CK-We are commanded to love one another as Jesus loves us. We can use the same romantic/poetic words for saints on earth and heaven just as long as Jesus is first in our heart and the understanding it’s all only possible because of God.

By the way, if you tell your spouse you love her with all your heart do make sure to add but I love Jesus more to clear things up for Him?

CK–

I was extremely tired when I wrote these words, and I worried that you might not get the point…and clearly you didn’t.

You can’t honestly tell me that words never matter, only the intent of the heart. Why don’t we just dispense with words then? They’re not important.

You cannot say “I hate your stinking guts!” in a loving manner. You cannot say “I magnify your name, O Queen of Heaven” in a non-deifying way. (I simply don’t care what your supposed intention is. It’s not enough to offset what you are actually saying!)

And just to be clear, my wife is ever so aware of my love for her relative to my love for Christ…and she wouldn’t have it any other way.

I wonder how you would read the 45th Psal m–is it purely allegory, or was it a real “song of love” i.e. wedding song, that carried a double meaning (i.e. it was about both the king’s wedding, and it was an allegory of Christ and His Bride. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Psalm+45&version=NASB

CK–

I was extremely tired when I wrote these words, and I worried that you might not get the point…and clearly you didn’t.

You can’t honestly tell me that words never matter, only the intent of the heart. Why don’t we just dispense with words then? They’re not important.

Me- no I’m not saying that at all!!! You are implying there are words like “save” can only be addressed to God. If I’m saying save me to God it’s worship if not then it’s not worship. You may be confused by it, but God is not because he knows my heart.

H-You cannot say “I hate your stinking guts!” in a loving manner.

Me- you are correct. That sentence only has one meaning unless you have a smiling emoji after it. 🙂

H-You cannot say “I magnify your name, O Queen of Heaven” in a non-deifying way. (I simply don’t care what your supposed intention is. It’s not enough to offset what you are actually saying!)

Me- yes you can! Luke 1:46-55 King James Version (KJV)

46 And Mary said, My soul doth magnify the Lord,

We are partakers in the body of Christ. Mary magnifies the Lord and we can magnify her name. I can magnify your name without worshiping you!

Jesus is the King that makes His mother the mother Queen. I don’t have to worship her to call her Queen anymore than I need to worship her to call her the mother of God. So if I prayed to her “Mary, mother of God, pray for me.” It would not be worship.

H-And just to be clear, my wife is ever so aware of my love for her relative to my love for Christ…and she wouldn’t have it any other way.

Me- God is ever so aware of my love for Him so that I don’t have to verbally qualify all my prayers.

In thy bounteous wisdom, Craig, guide me to the path of repentance. Unless thou deign to assist me, I fear I shall never set foot upon that path again! Thou art all I ever aspire to be. Thou art all I need to get me through. I throw myself upon the unfathomable riches of thy mercy, seeking and imploring thy grace.

By thy prayers, deliver me from my sin, and in thy power, rescue me from the Evil One! For thou art the very embodiment of compassion and charity. O, holy and incomparable St. Craig of New England, remember me in my plight and take pity on me!

We are going in circles. You already know that such hyperbolic language was employed in purely secular contexts in the middle ages, which is when the prayers you don’t like originate.

Craig–

Sorry. Should have included a smiley face or two!! 🙂 🙂

Craig–

As Peter said, that may be fine for the historically astute, but it’s unquestionably dangerous for those with less sophistication.

King Hezekiah knew better than to retain the bronze serpent Nehushtan despite its historical legitimacy.

So work to change the over-the-top content of IOS prayer, or lose my vote as to your own personal theological integrity.

(And, for what it’s worth, the higher and thicker hyperbole is piled, the more it becomes a flat-out lie. Hyperbole is to be used sparingly or it loses its effect.)

“As Peter said, that may be fine for the historically astute, but it’s unquestionably dangerous for those with less sophistication.”

Wonderful. Jesus specifically cautions us about wealth but not specific words. I take it you are as passionate in telling those you believe have too much money or strive to make more money than they need to feed and shelter themselves to take a vow of poverty because wealth makes it harder for one to be saved. I’m sure you as a man of God has taken such a vow. Why risk it?

As a matter of fact everyone should take a vow of poverty, specially those with less sophistication!

CK–

So sorry to burst your bubble, but I am, by first-world measures at any rate, pretty poor. Something like 105% of the poverty line (just barely over). My kids are on Medicaid and WIC. (How poor do I need to be before you will absolve me of hypocrisy?) Quite honestly, I have no need of and no desire for material wealth. I tend to agree with John Wesley that we should “make as much as we can, save as much as we can, and give as much as we can.”

I don’t give Catholics grief over calling priests “father,” but I don’t see them caring or even trying to figure out what Christ meant in saying what he did. It’s as if they’re above all that. They have some sort of privileged status in the kingdom of God which exempts them from the need to study the words of Christ.

I find it funny that this argument is reduced to that the traditional side is technically correct but they haven’t updated their verbiage and so we got to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Not sure why you think you are bursting my bubble. There’s a difference between being poor and taking a vow of poverty.

H-I don’t give Catholics grief over calling priests “father,” but I don’t see them caring or even trying to figure out what Christ meant in saying what he did. It’s as if they’re above all that. They have some sort of privileged status in the kingdom of God which exempts them from the need to study the words of Christ.

Me- Comments like this show your blind distaste for Catholics.

Maybe if Protestants spent more time trying to understand what Christ meant instead of wasting their energy misrepresentating Catholic beliefs they would figure out that Christ did not literally mean call “no man” father.

We can do better studying the Bible but at least most of it is read at mass. Most Protestants know nothing about the Church Fathers, could care less or have no understanding of the communion of saints, and focus only on their personal relationship with Christ, that is also dangerous.

“I find it funny that this argument is reduced to that the traditional side is technically correct but they haven’t updated their verbiage and so we got to throw the baby out with the bathwater.”

I agree. And this is one of the reasons why RCC continues to write important documents in Latin. Because it’s a dead language the meaning of the words are the same today as a thousand years ago and a thousand years from now.

Craig–

I find it extraordinarily sad that you find it “funny.”

Technically correct? Are you freaking kidding me!!!!! No, no, a billion times no, you do not have it even slightly “correct.”

You don’t have a baby in that filthy, liquid stench. Throw it out already!!!

Craig–

Are you seriously trying to tell me that you pray allegorically? This sounds like another logical end around. It sounds like either self-justification, self-denial, or both.

CK–

In your view, could I get away with calling Pope Francis the “Antichrist,” as long as I assured you that I meant only that he was not personally Christ himself? My intentions would be altogether righteous….

Yes, there are historical objections and whatnot. But in spite of that, my heart is good. I mean no disrespect whatsoever. Trust me.

H-In your view, could I get away with calling Pope Francis the “Antichrist,” as long as I assured you that I meant only that he was not personally Christ himself? My intentions would be altogether righteous….

Yes, there are historical objections and whatnot. But in spite of that, my heart is good. I mean no disrespect whatsoever. Trust me.

Me-no is not what I’m saying and you know it. You’d be using a word that expresses the opposite of what you believe. Antichrist is not and has not historically meant “one who is not personally Christ himself”. Otherwise everyone could be referred as the Antichrist.

I venerate the Saints and ask for their intersession. I use middle English prayers to express my love and make requests and even praise them. Historically it was never a worship prayer. I know any abilities they have is through God. They are creatures not gods. So to summarize, prayer/praise/thanksgiving to God is always worship otherwise it’s not.

So, my prayers express what I believe and feel in my heart. The saint’s are not God and therefore it’s not worship. God is not going to be mad because he knows in my heart and words I give the ultimate glory to HIM and don’t deny the gift He gave us when we participate in the communion of saints.

You keep insisting on forcing your modern definition on me like you are some kind of authority.

God knows exactly what I mean and intend with my prayers because he knows my heart. That’s my point. Your example above is nonsensical.

Craig,

You claim that Hans andI have reduced this argument to the “traditional side” being technically correct but not have updated their verbiage.

In The earliest tradition, we have no record of the apostles and the ante nicene fathers using verbiage “Mary save us”. That verbiage is later and it is the bath water not the baby.

Also, your statement is logically problematic as well. The jehovah witness are technically correct in accepting the bible as the inspired word of God, but you and I would never accept their new world translation as a valid translation because seriously distorts the Greek.

Ck,

Words matter! Jesus had some pretty strong stuff to say about idle words. Should we baptize in the name of creator, preserver, and sustainer instead of father, son and Holy Spirit if words don’t matter? Would I be legalistic if I defend the trinitarian formula? How about addressing the Lord as “hey good buddy” instead of “our father”?

I don’t deny that there are those who can be legalistic and quite annal about words. But my opposition to the Marian prayers defended on this website hardly qualifys for that. God indeed looks at the heart, and he knows how all of us are prone in our hearts to other “gods”.

“Lord Jesus Christ, son of God, have mercy upon me a sinner” I have/do pray often.

“Mary save us”, not going there!

Peter-In The earliest tradition, we have no record of the apostles and the ante nicene fathers using verbiage “Mary save us”. That verbiage is later and it is the bath water not the baby.

Me- what is your cut off? Do you only follow teachings from the fathers in the ante nicene period? So if it’s not addressed during that period throw it out? I’d love some consistency on this from you.

H-CK,

Words matter! Jesus had some pretty strong stuff to say about idle words. Should we baptize in the name of creator, preserver, and sustainer instead of father, son and Holy Spirit if words don’t matter? Would I be legalistic if I defend the trinitarian formula? How about addressing the Lord as “hey good buddy” instead of “our father”?

Me-I never said words don’t matter at all. Please stop with the hyperbole. In this case He gave us a specific formula. If we continue with your thought process we should only pray the Lords’s prayer…

P-I don’t deny that there are those who can be legalistic and quite annal about words. But my opposition to the Marian prayers defended on this website hardly qualifys for that. God indeed looks at the heart, and he knows how all of us are prone in our hearts to other “gods”.

Me- yes. As asked Hans did you take a vow of poverty? Jesus specifically warns about the difficulty those with wealth will have. We are prone to sin, but just because something good could possibly lead to sin doesn’t mean it should be avoided.

P-“Lord Jesus Christ, son of God, have mercy upon me a sinner” I have/do pray often.

“Mary save us”, not going there!

Me- then don’t.

Ck,

I was simply responding to Craig’s assertion of a traditional argument, when the earliest tradition did not have what I referring to. I am not biting the hook on your question of cutoff dates. It is divergent question. It is like person who finds roaches in his house when they weren’t there to begin with. The time he discovers the roaches or the exact time the roaches came in are irrelevant to fact they weren’t there to begin with.

You accuse me of hyperbole on the words matter issue. But yet you used the term “legalistic”, what do call that?

I am not disagreeing per se with you Wealth analogy. Granted, just because something is good does not mean it should be avoided just because it could lead to sin. There is use and abuse. However, the point I have been making is that the Marian prayers defended on this website is on not on side of legitimate use.

Peter I cannot agree with you because the real issue is whether we can ask Saints for intercession how we ask him is a matter of the society and the language

How we ask makes all the difference. You and both believe in going to the lord in prayer, but you and I would approach him with language such as “hey, dude, how’s is going”. Such address is not appropriate for him. Neither is it appropriate to address saints using language that is appropriate for God.

I believe prayers to God always are contextually different to the saints. I cannot offer you objective proof.

Grammatical correction from previous post, meant to say “wouldn’t approach”

CK–

Neither I nor Scripture have any problem with material wealth, per se. But the Bible does condemn needless hording. I am not only poor but have no intention of ever accruing wealth. I’m not going to take a vow of poverty on the basis of its being sinful…because it’s not. What I am going to do is stay true to a vow of sharing. And I HAVE confronted friends about spending too much on themselves.

From the way you posed the question, my guess is that you have way more than you need and are seeking to justify yourself.

The scriptures also say if you don’t work you don’t eat so if you’re taking food stamps it doesn’t hurt to try to make some more money

Just sayin

I wish society in general would embrace it.

Craig–

Actually, 2 Thessalonians 3:10 says that those who are UNWILLING to work, shouldn’t eat.

I think you’d be better off keying in on 2 Corinthians 8:14.

“Your abundance at the present time should supply their need, so that later their abundance may supply your need, that there may be fairness.”

You’re assuming for some reason that it is an option for me to work at the present time. It’s really not. (And to tell the truth, I do work–a lot–I just don’t get paid for it.)

Are all the poor to you lazy, good-for-nothing frauds?

Never was saying anything of the sort, but one should not purposely be poor and then require the generosityof others without exchanging some sortof service. Whether this is u r not i dont know

Not at all. I would embrace more wealth.

I was just trying to loosely tie back to some comments implied that the prayers to saints can lead to other things or how it looks to unsophisticated Christians etc…. Don’t drink, don’t dance!!!! It can lead to sin!

CK–

My analogy was INTENDED to be nonsensical. Because that’s what I find your explanation to be…nonsensical (and that’s why I don’t care what your intentions are).

There are, by the way, historical definitions of “antichrist” that don’t involve some demonic Dark Lord. It can simply be someone who is deceived and, as a result, opposed to the one true church. In this sense, Pope Francis is indeed an antichrist.

Do you remember the bumper stickers that declared the driver of the vehicle to be Pro-choice: Pro-child? I think we can both agree that this sentiment was pure hogwash. But their “intentions” were good!!!!

You pray prayers to saints, knowing full well that they are “creatures, not gods.” But then you treat them like gods and goddesses!!!! And WHY?? No one is forcing you to use these kinds of prayers. You can remain a Catholic in good standing without uttering a single one. But YOU LIKE THEM!! You LIKE flirting with idolatry!! It gives you a thrill or something. It’s the only logical explanation available.

H-My analogy was INTENDED to be nonsensical. Because that’s what I find your explanation to be…nonsensical (and that’s why I don’t care what your intentions are).

Me-doesn’t sound very Christ like, but hey you be you.

H-There are, by the way, historical definitions of “antichrist” that don’t involve some demonic Dark Lord. It can simply be someone who is deceived and, as a result, opposed to the one true church. In this sense, Pope Francis is indeed an antichrist.

me- I’m not intellectually corrupt as to try to force you to use the definition I prefer and pretend it has no other meaning. So know plenty of people who think the Pope is the antichrist and they have good intentions. I happen to think they are wrong. You of course don’t care what the intentions are (even when explained) and just assume it’s nefarious. Not good Christian behavior.

H-Do you remember the bumper stickers that declared the driver of the vehicle to be Pro-choice: Pro-child? I think we can both agree that this sentiment was pure hogwash. But their “intentions” were good!!!!

me-a person can have good intentions and be wrong. Maybe they have been told that the fetus is not a baby or just never thought the whole thing through. You don’t know.

H-You pray prayers to saints, knowing full well that they are “creatures, not gods.” But then you treat them like gods and goddesses!!!!

Me-I treat them special because they are special. Mary is special.

H-And WHY?? No one is forcing you to use these kinds of prayers. You can remain a Catholic in good standing without uttering a single one. But YOU LIKE THEM!!

me-True. I don’t have a very strong devotion to any saint, but I do pray to Mary.

H-You LIKE flirting with idolatry!! It gives you a thrill or something. It’s the only logical explanation available.

me-becoming closer to the my brothers and sisters in heaven and earth does give me a thrill.

I can say you Hans like flirting with (insert anything that can lead to sin). It gives you a thrill or something.

I gave you logical explanations you just don’t care. That’s on you. Remember I’m not the only one that doesn’t see anything wrong with it. St Thomas Aquinas (who knew theology almost as much as you) was good with it. I’m in good company.

CK–

1. I should have said that my analogy was ABOUT nonsense. There’s nothing unChristian about calling nonsense “nonsense.”

2. You wrote that “a person can have good intentions and be wrong.” Thanks for making my point for me.

3. You gave me some logical explanations you say. Really? You must have slipped those past me.

4. You say that Thomas Aquinas agrees with you. Are you sure about that? Check out the Supplement to his Summa Theologica, Question 72. He makes it VERY clear that all we are to do is to ask the saints to pray for us. I brought up a Marian prayer of his, and it is chock full of phrases like “obtain for me,” “request for me,” “with your assistance,” “by your prayers,” and “according to the will of your beloved Son.” Also, the honorifics are toned down considerably. He uses adjectives like sweet, tender, and merciful to describe her.

2. You wrote that “a person can have good intentions and be wrong.” Thanks for making my point for me.

Me- that’s the point of everyone commenting here! This is a waste of time if you think you have to explain this to me or anyone else here.

3. You gave me some logical explanations you say. Really? You must have slipped those past me.

Me- the reason some things slip past you is because you don’t accept our historical definition of words and “don’t care about intentions”. If don’t consider these then you can’t understand your interlocutor’s position . If you don’t understand your interlocutor’s position then productive dialogue is next to impossible.

So we get stuck on “pray”, “pray to” etc…

I believe we have discussed Sola Scriptura and how it doesn’t identify what books should be in it. To you SS takes into account some tradition and we went from there. Now imagine if I insisted that SS means Bible “alone” and nothing else! I’d be forcing my definition on you and we’d get nowhere. Much like our current back and forth.

CK–

Yes, a productive back and forth dialogue requires that we amend our understandings of the opponent’s position. But that requires that you EXPLAIN how my understanding of your beliefs is in error. I don’t care about your heart’s intentions because, as we both have agreed, your intentions can be good even though your actions are WRONG.

So explain to me how the over-the-top rhetoric in your prayers to saints benefits anybody at all. How is it necessary (even if your intentions don’t line up with your words)? Why not just say what you mean? (The Catholic Church isn’t insisting that you keep the hyperbole. This is YOUR decision!)

Because those in heaven are special and I honor them.

Your intention could also be wrong. You here for a reason. What is your intention?

My understanding of your position is that you believe certain words, accolades can only be used in worship no matter what the person means by it.

No, CK, that is actually not my contention. My contention would be more along the lines of your words displaying your true intentions, which are those of worship, despite your pretensions to the contrary.

And it is not individual words that bother me, but everything in context. You are making NO differentiation between the Creator and his creatures. And you have the temerity to be angry with us over that! (There’s no attempt at saying, “I can see why you guys are saying what you’re saying, but here’s why it’s not so. I’m as concerned about the potential of idolatry as you are.”)

You show absolutely no angst that you might possibly be offending God. That is NOT a humble, faithful response. You haven’t even given a reason for your acceptance of hyperbolic language. If you use the same language for saints as you use for God, then your words are either too special or not special enough. Honorifics should be true and appropriate or they are not particularly honoring at all.

If I were to pray “O glorious Osiris, I adore Thee,” and then maintain that I wasn’t being idolatrous–I just think Osiris is “special”–you’d call me out and say something on the order of “You’re daft!”

Well, that’s what I’m saying to you. Whatever is the nicest way of saying “You’re plumb loco.” I have read a ton of Marian prayers, and a whole lot of them are idolatrous. No ifs, ands, or buts about it.

Sounds like you are stuck on words. I think we’ve reached the end of the road on this topic. Btw I’m not angry at all.

God be with you.

Ck-

In your last response to me you stated that I supposedly don’t understand the communion of the saints. I assure you i have spent a lot of time reading and studying about this issue. This reminds how Roman Catholics are quick to accuse someone of denying or not understanding real presence in Eucharist if one does not subscribe to transubsiation.

I belong to a communion that names its churches after saints and has days set aside to honor them. I pray prayers that specify we are praying and worshipping with the church above. I affirm that they pray for us. Yet, you seem to stigmatize as being some baptist who advocates complete disconnect between Church militant and church triumphant. There is a paradoxical connection and separation between the two.

If “communion” is deduced to “talking to” then the saints ought to be addressing us as well. I am sure a departed saint has not talked to you lately.

You ask me if I affirm that they are praying for me then what do I think they are praying about. No matter how I answer that ,it is irrelevant as to invoking. One does not logically lead to the other.

You seem to be quite defensive that I am trying to stop you from IOS. You can not find anything in any of my posts where I condemn all IOS. Please go back to my original post.

My beef has been with the type of invocation that you and Craig defend. I believe that Hans and I have made our case clear.

I think we are at an impasse. My prayer is that this dialogue will generate more light and less heat. I will pray for you even though you have not asked me.

Peter–

What I don’t understand is Craig’s take on things. He has stated that Roman Catholicism definitely goes beyond the pale and that EO prayers sometimes make him uncomfortable, and yet he is dead set against any restriction on “verbiage.”

Hans-

I don’t understand it either. What I find also baffling is this defense of “mary save us” prayer by the EO, yet they rejects the term “co-mediatrix” for Mary. They claim that it is inappropriate and causes confusion.

I dont think comediatrix is a big deal. She mediates by her prayers though not her sufferings which is blasphemous as supported by some RCs.

She mediates by her prayers though not her sufferings which is blasphemous as supported by some RCs.

Me- We can unite our suffering to Christ but I never heard of Mary mediating through her sufferings. How could she do this if she is no longer suffering? I agree with you unless I’m missing something. Do you remember where you read this?

Some Roman Catholic writers in the mid-twentieth century speculated that her anguish at the cross watching her son die had some sort of a toning effect

Remember i am a protestant convert. I cannot instantly become cradle Orthodox in my language anymore than a esl speaker will suddenly perfectly know the english.

Craig–

I don’t think “mediatrix” is the issue so much as the “co.” Whatever she does by her mediating prayers cannot be made equivalent enough to give her co-billing.

Remember what it says in 1 Timothy 2?

“For there is one God, and one mediator also between God and men, the man Christ Jesus.”

Whatever “mediator” means there, Mary is necessarily left out of the equation.

Well, Orthodox do not teach the doctrine, nor do Roman Catholics explicitly. Personally, I don’t think such terminology would be totally out of line as long as contextually the idea was not to put Mary’s mediation on par with the cross.

We do not do “the sign of Mary” after all.

God bless,

Craig

No, CK, I’m stuck on concepts. You seem to be of the opinion that words and concepts don’t need to correspond to one another as long as you feel good about it:

“War is peace. ”

“Freedom is slavery. ”

“Ignorance is strength.”

At any rate, I bear you no ill will either. And, just so you know, it would be difficult for me to live my life if I had a fervent distaste for Catholics.

My doctor is Catholic. My dentist and pharmacist and postman are Catholics. My kids therapists and social workers are Catholic. The wonderful lady who weekly helps us out with our kids’ laundry is Catholic. And the great guy living right across the street from me who’s running for city council is Catholic. One of his campaign signs is firmly planted in my front yard.

Hans-

I don’t understand it either. What I find also baffling is this defense of “mary save us” prayer by the EO, yet they rejects the term “co-mediatrix” for Mary. They claim that it is inappropriate and causes confusion.

Peter:

I’m with you. It beggars belief. Not only do they not see it, but they don’t even comprehend our concern!

The EO actually call the Theotokos their Sovereign Lady. How can that NOT be misunderstood? Who is Sovereign over all the cosmos, all the world, and time? What’s left for Mary to rule? Why are her titles EQUAL to Christ’s (Lord = Lady, King of Heaven = Queen of Heaven)?

From an Akathist honoring the Virgin:

“O Sovereign Lady…

No one goes away empty-handed from your inexhaustible cup, O merciful one, but all are filled with divine gifts; so that having received healing and help, they may sing to you: Alleluia!”

****************

And it’s quite clear from the punctuation and the context of the rest of the prayer that they’re singing Alleluia TO Mary (not just in her presence but directly to her). Don’t they understand that this word means “Praise be to God”?

And here’s a similar Catholic prayer:

“O my Sovereign Lady!

O my Mother!

I offer myself entirely to thee,

and to prove my devotion,

I consecrate to thee my eyes,

ears, mouth, heart, and my entire being.

Since I belong to thee, O good Mother,

guard me and defend me

as thy very own property and possession.”

****************

This is reminiscent of John Paul II’s motto of “Totus Tuus” (totally yours) reputed by some to be his final words. How is THAT not “totally” confusing? You dedicate yourself ENTIRELY to Mary?

(And yes, I’ve heard their explanations. But these would need to be COMPELLING in all caps, and they simply are not.)

I would take issue with that prayer as it is translated simpky because alleluia means praise God in Hebrew. That can only be said of God. Being that i have never seen that prayer nor know of its usage in which prayer service i cannot pass a more intelligent comment. I know for a fact that a lot of these are bad english translations. My godfather told me about cleaning up the translation of the russian for a prayer because the english translation was wrong and made it seem like we worship Mary.

Hans your latest response is why I know you could care less in trying to understand my position. I can tell you are intelligent. So I don’t understand why you completely butcher my position and set up straw men. It’s hard to even consider if your position is correct and mine is wrong when you purposely misrepresent mine. You say your stuck on “concepts”.

I gave my concepts earlier. I am posting it again below.

XXXXX

“You say saints pray for us. What could they be possibly be praying for? What is their ultimate goal when they pray for us? In Hebrews we are told we are surrounded by witnesses. They are encouraging us on in this race. They are are playing their part in saving our souls.

What is your goal by getting me stop praying to the saints? What are you trying to do for me? You are playing what you believe is your part in saving my soul.

All this grace comes from God and he will be the ultimate judge. But we are called to help one another. God doesn’t care how I come to Him in the end because it’s through His Grace working through you or Mary etc…. All the glory belongs to Him and all grace flows from Him.

Those in heaven will be playing a role in our judgment. Of course the King will have the final say.

Do you not know that the saints will judge the world? And if the world will be judged by you, are you unworthy to judge the smallest matters? Do you not know that we shall judge angels? How much more, things that pertain to this life? (1Cor. 1Cor. 6:2-3).

4 I saw thrones on which were seated those who had been given authority to judge. And I saw the souls of those who had been beheaded because of their testimony about Jesus and because of the word of God. They had not worshiped the beast or its image and had not received its mark on their foreheads or their hands. They came to life and reigned with Christ a thousand years. Rev 20-4

So with this understanding I can say you can save me as can Mary as instruments of God. This is the communion of saints.”

XXXX

I know Craig can do a much better job explaining this, but this is my best attempt. Now after I take the time to try to explain it, you are still saying my position amounts to this:

“War is peace. ”

“Freedom is slavery. ”

“Ignorance is strength.”

We should be well past these kinds of comments, but here we are.

That is not my position and you know it. Your intelligent enough but seem not to want to understand my position and so it is fruitless to continue. I know you have good “intentions” but….

CK–

This is an emotional response on your part with no substance to it. That said, I can easily relate to your sentiments. I have spent tens of thousands of hours in discussion with Catholics. It has been mind-numbingly frustrating to say the least. Emotionally, I could confide in you that, in my experience, Catholics are incapable of good faith dialogue. That’s my emotional response. But if I take a step back, I realize that interfaith conversations are just inherently difficult. People have a heckuva lot invested in their religious convictions.

I take part mostly to learn. I have no expectations that anyone will listen to me. So often these interactions become a game of one-up-man-ship. I’m not in it to score points. And I don’t want anyone to win. I root only for the truth, and champion its cause and its cause alone.

I haven’t asked you to quit praying to the saints. I have merely asked you to quit praying to them as if they were gods and goddesses. We could take all kinds of Catholic prayers and switch out the names: replace Christ with Mary or Mary with Christ. No one would be the wiser.

Given your argument, what specifically would be wrong with praying thusly:

“Holy Mary, Redeemer of mankind. You and You alone can save us!”

You’ve already stated that she is part of the redemptive process, so asking her to save us is perfectly fine. Consecrating oneself to her and her alone is also perfectly fine, so I would surmise that my wording is basically ok and would raise no red flags. And yet, as I hope you can see, to say it’s okay makes a mockery of language!

How about this?

“O Mary most high, robed in unmatched majesty, goddess of the universe, give heed to my urgent request for your aid.”

Is the word “goddess” out if my heart is right? If I know that any power she has is derived from God himself? Is ANY word ruled out by you (as long as one’s heart is right)? Is prostration in (if my heart is right) even though it is ruled out in Scripture (no bowing to the Apostles)?

My point in using the quotes from the book “1984” was just that: you seem to be able to employ any word you choose, even if it means the opposite of what it’s supposed to mean, and transform it into the right word by the machinations of your magical heart.

Hans tell me where you are getting all these prayers from. Never heard of calling her a goddess etc… please provide a link.

Hans-you seem to be able to employ any word you choose, even if it means the opposite of what it’s supposed to mean,

Hans seriously stop the nonsense. Please show me where I said this specially the “even if it means the opposite of what it’s supposed to mean,”

In my next to last post I just told you that is not the case. You call yourself a Christian yet continue to LIE about my position.

Actually forget it. You obviously have no intention of being charitable.

God bless.

CK–

Perhaps I have fumbled the communications on my end. Perhaps you have had trouble following along (because of my fumblings or for other reasons). Do you know EXACTLY where the breakdown has been? Because I don’t.

Accusations of uncharitability when we cannot even pinpoint where things went wrong…are themselves uncharitable. I’ll try to be more careful if you will.

I probably shouldn’t have said that you endorse meanings for words in direct opposition to their commonly accepted meanings. That was hyperbole.

But what I meant to say is difficult to communicate. Sometimes two meanings of a word can be on entirely different planes of thought. For God to save us from sin and (second) death is entirely different from a lifeguard saving us from physical death by drowning. And that is completely different from “saving” a term paper from your kid brother’s feeding it through a paper shredder.

J. K. Rowling wrote the Harry Potter series completely ON HER OWN. Nobody cowrote it. Nobody assisted her in writing it. Only HER name appears on the cover.

And yet many were involved in the process: editors, agents, publishers, typesetters, publicists, distributors, booksellers, lawyers, software writers, etc.

Being “involved in the process” is on a whole different, uncredited plane. In this sense, it is uncredited and nonessential. In other senses, it can be considered credited and essential. But they are on totally different planes. The underlings, in general, receive NO residuals. Rowling alone gets to sell the film rights. She wrote the book, and they did not.

Though Mary may be involved in the process, God and God alone saves us. These two actions are on completely different planes (which is why I hold to monergism …and why I believe synergism is confused).

In the early church, believers were called upon to deny Jesus and to worship the Emperor. Those who gave in because they valued their lives more than staying faithful to the cause of Christ, did not deny him in their hearts, but before men. In their heart of hearts, they didn’t actually even respect (let alone revere) the Emperor. And yet they were counted faithless for their actions!

I don’t think you’re at all a liar concerning all this. Just confused and wrong. I am sorry if I hurt your feelings. It wasn’t intentional.

Hans- Accusations of uncharitability when we cannot even pinpoint where things went wrong…are themselves uncharitable. I’ll try to be more careful if you will.

Me- I pinpointed exactly what my issue is. If you still think I’m saying using words that have the opposite meaning of what one is trying to convey is ok, then our back and forth is a waste of time.

Hans- I probably shouldn’t have said that you endorse meanings for words in direct opposition to their commonly accepted meanings. That was hyperbole.

Me- actually hyperbole usually has some grain of truth. I can say I worship my wife when in fact I mean honor her. Hyperbole would is not saying I hate my wife when in fact I mean I honor her.

Hans- But what I meant to say is difficult to communicate. Sometimes two meanings of a word can be on entirely different planes of thought. For God to save us from sin and (second) death is entirely different from a lifeguard saving us from physical death by drowning. And that is completely different from “saving” a term paper from your kid brother’s feeding it through a paper shredder

Me- I know that you are communicating this point and you are correct. The reason its ok to say “save” or “save us” in the examples you provided above is because we understand in what CONTEXT it’s being used.

Hans- J. K. Rowling wrote the Harry Potter series completely ON HER OWN. Nobody cowrote it. Nobody assisted her in writing it. Only HER name appears on the cover.

And yet many were involved in the process: editors, agents, publishers, typesetters, publicists, distributors, booksellers, lawyers, software writers, etc.

Being “involved in the process” is on a whole different, uncredited plane. In this sense, it is uncredited and nonessential. In other senses, it can be considered credited and essential. But they are on totally different planes. The underlings, in general, receive NO residuals. Rowling alone gets to sell the film rights. She wrote the book, and they did not.

Me- Actually, without the people “involved in the process” we would not have ever heard of her. Nonetheless I get your point. She is the ultimate source of the book and all the glory (of the flesh of course) goes to her. She doesn’t care to share the glory and that’s why we don’t know about the people involved in the process.

Hans- Though Mary may be involved in the process, God and God alone saves us. These two actions are on completely different planes (which is why I hold to monergism …and why I believe synergism is confused).

Me- I agree. God alone saves us because He is the source, but God chooses, actually demands that all the members of His body participate in His ministry. God alone is the source of life yet He allows a man and a woman to participate in creation. It’s not monergism otherwise there would be no need for humans to perform an action for a new creation. Without Jesus there is no salvation, but we are all asked to participate in the salvation of one another and ourselves through free will. This is synergism.

Hans- In the early church, believers were called upon to deny Jesus and to worship the Emperor. Those who gave in because they valued their lives more than staying faithful to the cause of Christ, did not deny him in their hearts, but before men. In their heart of hearts, they didn’t actually even respect (let alone revere) the Emperor. And yet they were counted faithless for their actions!

Me- so you mean they lost their salvation? 🙂

Ok but when I’m saying God knows my heart, I never meant that my prayer can be in opposition to what I mean. What I’m saying is the prayer in “CONTEXT” means exactly what I’m trying to convey. You hear the word “pray” and to you it means “worship God”. Pray in middle English means “request” just like “worship” in middle English means “honor”. The CONTEXT used determines if it’s worship or not.

Hans- I don’t think you’re at all a liar concerning all this. Just confused and wrong. I am sorry if I hurt your feelings. It wasn’t intentional.

Me- You didn’t hurt my feelings at all. I don’t know you. I just don’t like wasting time.

CK–

I’ll try again. The problem is most certainly NOT context. It is wrong usage on your part, and I have trouble understanding why you can’t see that. If we consulted a disinterested third party to judge between us, your side would lose ten times out of ten. It’s not ambiguous. It’s not debatable.

You cannot tell J. K. Rowling’s publicist or distributer that you absolutely LOVED those books they wrote about wizards and muggles and dementors and horcruxes. They simply DIDN’T write them!! And it doesn’t matter if you’re such a close personal friend of Rowling’s that you call her “Jo.” No CONTEXT will ameliorate things. You’re just plain in the wrong.

My wife did not redeem me…though she is part of my process of redemption. No faith healer actually heals. They’re merely a conduit of divine power.

“To save” and “to be a part of the salvation process” are two very different things.

If God alone saves us, then what we have is monergism. You can’t tack things on and say “God alone.” He is no longer alone. You’re trying to hold onto two contradictory things and have them both be true. It doesn’t work that way.

Not every Catholic agrees with you, by the way. Fr. Robert Barron, for example, speaks not of Sola Gratia but of Prima Gratia. We are first and foremost saved by God’s work and God’s grace, but not exclusively.

Monergism does NOT mean that only God works. Good works are part and parcel of every orthodox Protestant system. Our works are simply on another plane. Our works are contingent. His Providence is paramount.

*************

After I had written this, I stumbled across a couple of NT verses for which I will have to answer. Romans 11:14 and James 5:20. Both use the word “save” by itself to describe instances where individuals lead other individuals to conviction and repentance and thus into the arms of Christ. These are, then, examples wherein the context allows us to see that though these individuals did not directly save others as God might, they were indeed involved in a process which resulted in another’s conversion and salvation.

So, should I capitulate to your argument?

I don’t rightly think so. Let me explain why.

Take another similar NT passage from 1 Corinthians 7:

“For how do you know, wife, whether you will save your husband? Or how do you know, husband, whether you will save your wife?”

Basically everyone reads this text as describing an ability to evangelize others, not to actually save them.

If you want to pray to Mary, then, to evangelize you or someone else, go right ahead. Perhaps she has access to do exactly that. What she cannot do is save us. And a straightforward request to save can never mean simply to evangelize.

“How do you know whether you will [persuasively evangelize] your wife.”

That’s a fill-in-the-blank that I can buy.

“O holy Mary, [persuasively evangelize] us, we pray!”